Two days ago, Judi Terzotis, Gannett’s newly minted president of its newly created Gulf Region Division, wrote the obituary for a 134-year-old daily newspaper that, in its heyday, had been one of the most influential and innovative journalistic institutions in the entire country, The Town Talk of Alexandria, Louisiana.

Terzotis can be forgiven for not appreciating the magnitude of her announcement. She has only been on the job for about a year, and The Town Talk is just one of several mid-market papers for which she is responsible.

It’s also worth nothing: She’s apparently never actually lived in Alexandria. She also heads up the Lafayette Daily Advertiser, and Lafayette has been her home for around three years.

Before that and during a brief break from Gannett, she was president of a paper in Fort Collins, Colo., for a couple of years, and before her gig in Fort Collins, she was an associate editor of a paper in Colorado Springs, which also lasted about two years. But eventually, Terzotis found her way back home to Gannett, where she had shuffled through three different jobs for three different papers in Mississippi and Tennessee in less than a decade.

All told, Terzotis has held at least eight different jobs in five states, almost exclusively with Gannett, during the last 19 years. I do not know Terzotis, but it sure sounds like she is a loyal and valuable utility player for Gannett corporate. She very well may be a kind, decent and intensely brilliant leader who has risen through the ranks because of her tenacity and her laser-like focus on the ever-bleaker financial spreadsheets and web traffic analytical reports.

I also fully understand how the ubiquity of free, online news has upended the traditional newspaper business model, forcing publishers — both big and small — to imagine more effective, more competitive, more targeted and more profitable strategies.

But, much like The Times-Picayune’s similar decision to switch to a three-day-a-week publication supplemented by a daily digital site heavily reliant on wire stories available almost everywhere for free (and therefore functionally obsolescent), I cannot help but lament the ways in which the blind rush to consolidate media companies, more than any other factor, murdered the local newspaper, which is not only a critical community institution; the local newspaper, more than anything else, continues to be the most important check against public corruption.

It is simply impossible to outsource stories about city hall or the school board or county commissioners or, in Louisiana’s case, police jurors to some national freelance reporter or some rookie straight out of high school. Local news-gathering and reporting relies on those who possess institutional expertise and those with a desire to learn it.

The local newspaper should be a community’s ears on the ground and its eyes on the streets, but the only way its reporting can be taken credibly is if it is informed by the oral histories of people who live there and the knowledge that journalists only gain by fully immersing themselves in the community, every single day. It’s not always glamorous work, and it rarely earns major national awards or commendation.

Today, Gannett owns a national daily, USA Today, and, until recently, 109 other local dailies all across the United States and 150 brands in the United Kingdom. Since its founding in 1906, Gannett claims to have earned a grand total of 56 Pulitzer Prizes during the last 111 years, between its 110 American newspapers.

But, notably, those numbers appear to be either highly inflated or deceptively counted. Gannett did win a Pulitzer for special reporting in 1964 and another Pulitzer in 1980 for its news service. Its flagship paper, USA Today, has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. In addition, The Virgin Island Daily News, under Gannett, won a Pulitzer in 1997; The Rochester Times-Union, one of the conglomerate’s first acquisitions, won the prize in 1971; The Observer-Dispatch, which was also one of Gannett’s very first properties, won a joint award for public service in 1959. The Detroit Free Press picked up a Pulitzer in 2014, with Gannett as a limited managing partner. And The Des Moines Register, which prior to its purchase by Gannett had earned more Pulitzers than any other paper not named The New York Times, managed to earn three additional Pulitzers in 1987, 1991, and 2010.

There are only two possible ways in which Gannett could claim it has earned 56 Pulitzer Prizes, instead of the 10 it has actually collected: Either Gannett is counting each and every recipient as winners of an individual award (and yes, very rarely, two or three journalists may share a prize for the same collaborative work), or, more likely, it's counting every previously awarded Pulitzer Prize won by every newspaper it would eventually own.

By contrast, The New York Times has won 119 Pulitzers; The Washington Post has 47, The Wall Street Journal has collected 39, and The Boston Globe has 26 under its belt.

Yet USA Today, Gannett’s most prized asset and the largest national newspaper in the entire country, with a circulation that is nearly the circulation of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal combined, hasn’t won even a single award. A 111-year-old media conglomerate with 110 American newspapers under its corporate umbrella has won journalism’s top prize fewer times than the Times, the Post, the Journal or the Globe. Politico and Huffington Post and even The Berkshire Eagle of Pittsfield, Mass., each have more Pulitzer Prizes on their mantles than the largest newspaper in the country.

And sure, you could argue that the Pulitzer is just an elitist and meaningless vanity prize and that USA Today has such a wide circulation because it better responds to consumer demand. But that ignores something blatantly obvious to anyone who lives in a community in which Gannett operates: They are systematically deconstructing and destroying local, community newspapers in order to subsidize their substandard, laughable, and vapid gossip rag posing as a legitimate national news source. There’s no serious reporting in USA Today. When is the last time USA Today actually broke — on its own — a story of profound national or international consequence?

When Joe D. Smith sold The Town Talk in 1996 to Central Newspapers, it’d been a family-held enterprise for 113 years. Scholars from all over the country were fascinated by what Joe D. had created in Alexandria; he was an innovator, decades ahead of his time. In 2005, Fredrick M. Spletstoser, an academic from Missouri, wrote an entire book about the early years of The Town Talk. (I’m glad I hoarded a few copies of this before it went out of print, because today used copies are going for $90 – $400).

Spletstoser recognized the symbiotic relationship between my hometown and its newspaper, and if you ever have the chance to read his book, take it. Even if you’re not from Central Louisiana, it’s a fascinating case study.

In 1996, when Joe D. sold the paper to Central Newspapers (which then sold it to Gannett), newspapers were already online, even in Louisiana. The Times-Picayune launched its first online site in mid-1995. Everyone in the industry understood that the internet had the ability to dramatically reorient the ways in which we receive and discern the news. But people also understood the value of the product that Joe D. Smith had built: A feisty little newspaper with a big voice.

The Town Talk sold for $62 million.

Shortly thereafter, Gannett pilfered every last penny from it. It outsourced the local printing press, leaving Downtown Alexandria with an enormous, vacant, blighted warehouse and stealing away dozens of good-paying jobs. It brought in a couple of high-priced executives who cared more about their next job in the next city than they ever cared about Central Louisiana. It fired dozens of career employees and award-winning journalists. It was too slow or too stupid to learn how to adapt to the internet.

And perhaps most critically, it never understood its own business, believing that local journalism could somehow be automated.

On May 13, 1864, Union soldiers burned Alexandria to the ground. At the time, Alexandria was the second-largest city in Louisiana and, ironically, a haven for Northern sympathizers. William Tecumseh Sherman had once lived directly across the Red River. It’d take decades before Alexandria fully recovered, and no one was more instrumental in guiding and cheerleading its recovery than an Irish immigrant who published columns on his own printing press extolling Alexandria as “the future great city.”

His name was Edgar McCormick, and along with his friend and fellow Irish immigrant Henarie Huie, he founded The Town Talk.

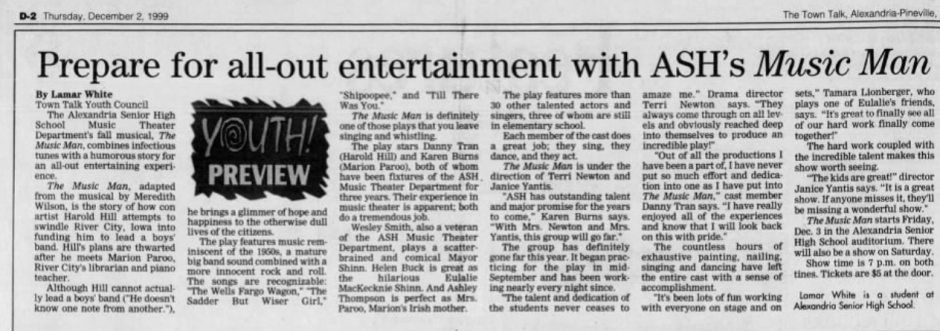

More than a century later, The Town Talk was the very first newspaper to ever print a column I’d written, as a member of its Youth Council. It was a glowing review of our high school’s production of The Music Man.

And even before that, The Town Talk was the very first newspaper to print my name in a story about someone else. I was the ring-bearer at my Uncle John and Aunt Erin’s wedding.

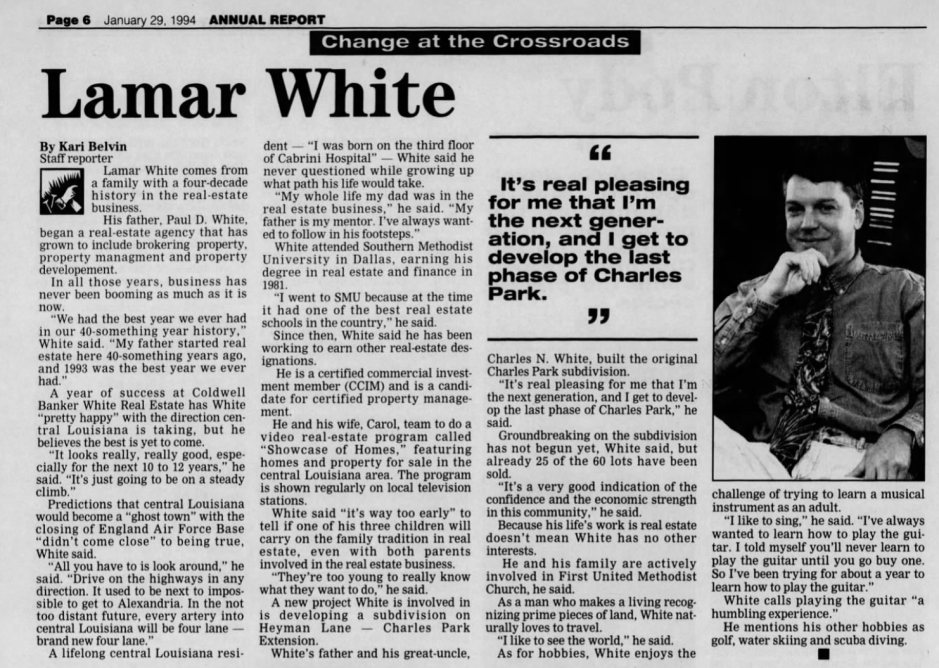

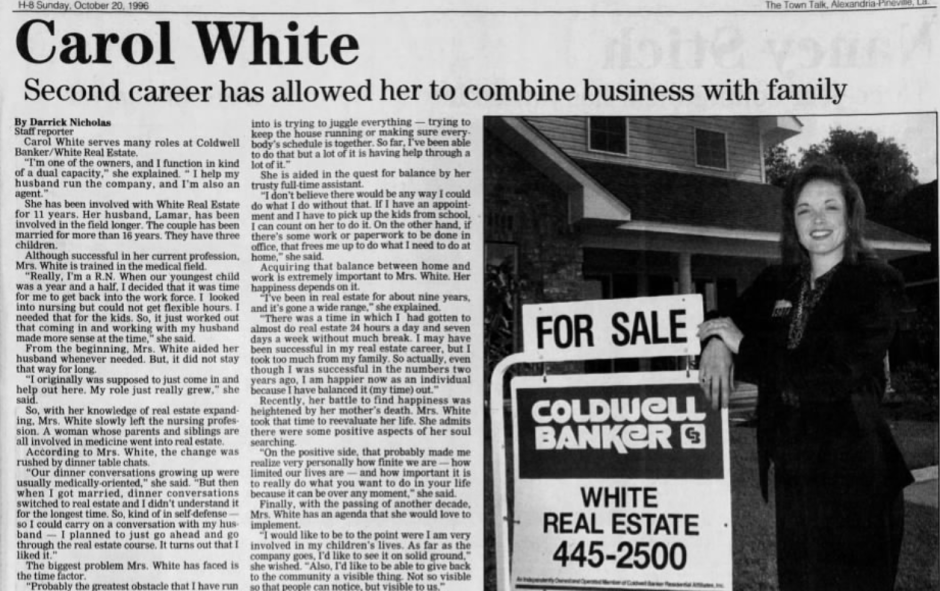

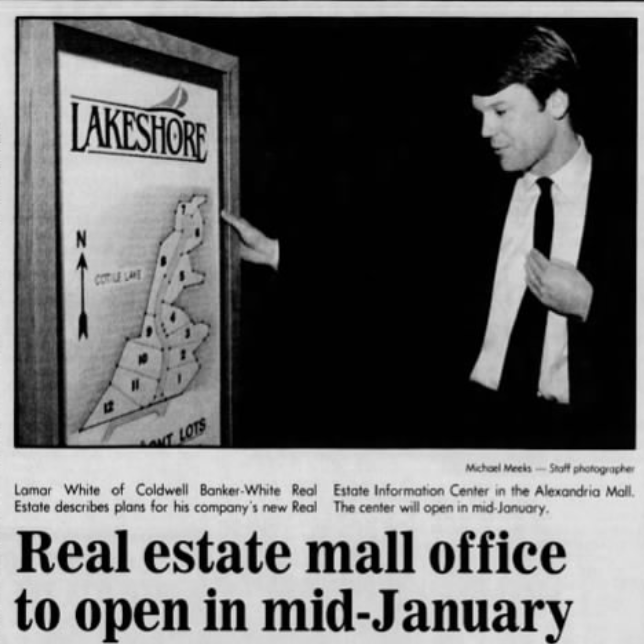

My mother and father owned a real estate brokerage firm in Alexandria, and over the course of 20 years, their names were printed in advertisements in The Town Talk more than 10,000 times. So, in a way, it is also a chronicle of their professional lives, which I could never fully understand as a child and which is all the more important to me since my father’s death in 2001.

I will always cherish little stories like these (apologies in advance to my mother):

And these too:

Because this is part of the magic of a good local paper: At its very best, it chronicles our lives, and people will pay to read that, no matter what.

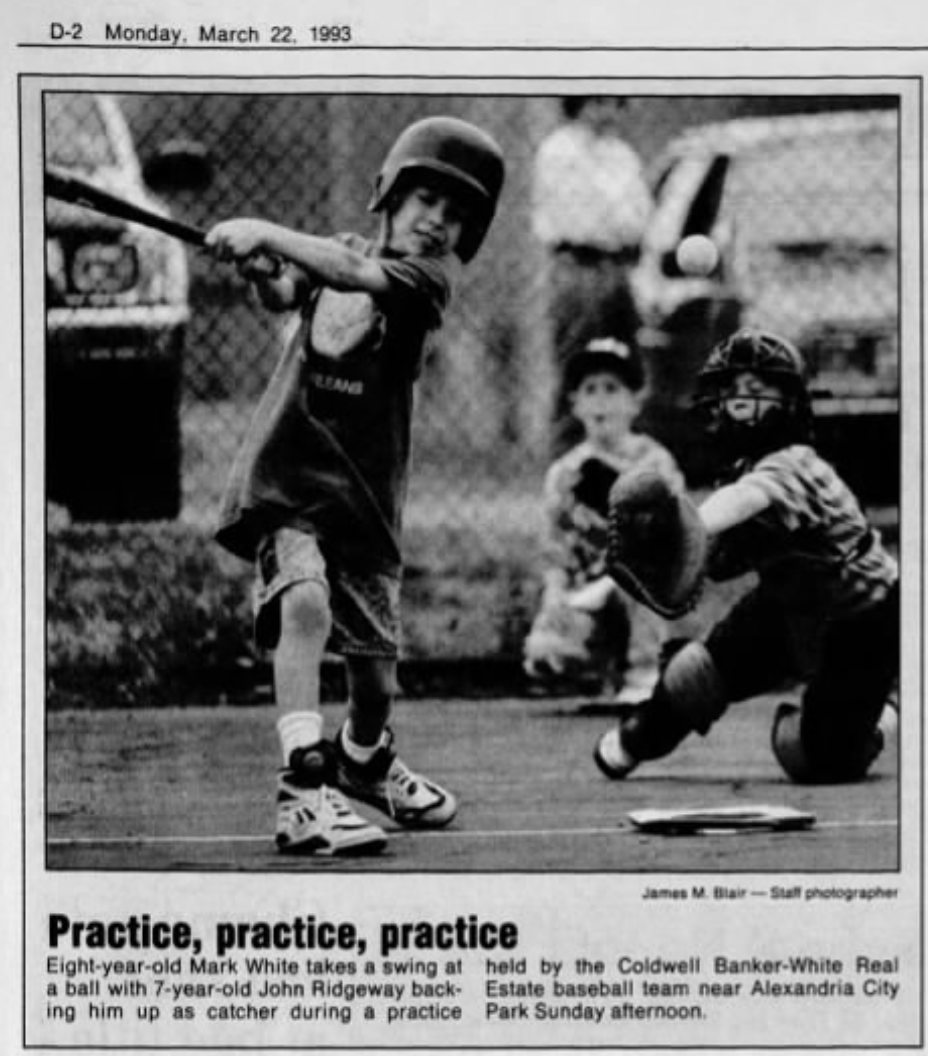

Here’s my younger brother Mark obviously swinging and missing at a pitch when he was 8 years old (to his credit, a few years later, he managed to knock out one heckuva home run.):

I understand there are certain stories that, nowadays, are better suited online, but it’s not nostalgic or sentimental to assert that there are many more moments — in the life of a community — that require the permanence of ink and paper.

If Gannett truly cares about the people of Central Louisiana, there’s a simple solution. Instead of eliminating our one and only daily newspaper, sell it back to the locals. Of course today it’s only worth of a fraction of the $62 million it sold for 21 years ago.

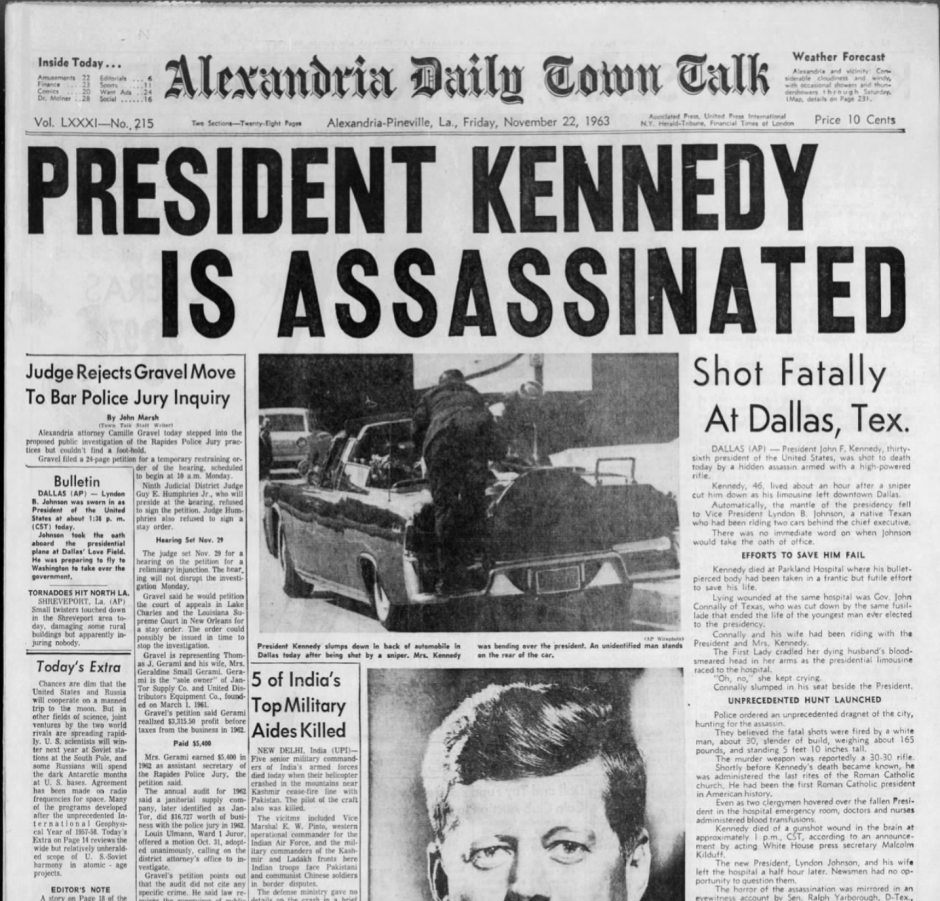

But for more than a century — through the aftermath of Reconstruction and the invention of radio and then television, through two world wars and devastating assassinations, through a race that finished on the surface of the moon and an Air Force base closure that threatened to destroy our local economy — the people from Central Louisiana wrote and published The Town Talk themselves. And year after year, it turned a profit.

Gannett isn’t failing in Central Louisiana because of the internet. It’s failing because it doesn't give a damn about spending money to create the one and only product it is uniquely capable of selling: The local news.